Civil protection of property rights

Protection of property rights in a broad sense is the focus of civil law norms on regulating property relations under normal conditions of use by the owner of his property without violating his powers, as well as without infringing on the rights and interests of other persons. Protection of property rights, i.e. protection of property rights in the narrow sense is a set of only those methods and means that are used when property relations (the rights and interests of the owner) are violated.

Methods of protecting property rights are traditionally divided into proprietary rights (absolute protection against everyone; applied in case of direct violation of property rights) and obligatory laws (relative protection against a specific violator; applied in violation of relative rights, when property rights are violated indirectly, for example, a tenant does not return the item after the rental period has expired). The remedies are lawsuits, since the protection of property rights is carried out through a lawsuit in court. The term “claim” in the field of property law has not only a procedural, but primarily a material meaning as a claim of the owner.

The system of civil legal remedies for the protection of property rights consists of: 1) proprietary claims; 2) claims aimed at protecting the interests of the owner upon termination of ownership by force of law; 3) claims under the law of obligations.

Claims in rem are claims directly aimed at protecting property rights, since their goal is to fully restore the rights of the owner in relation to specific property. Only the actually existing (already acquired and not yet lost) property right is protected by proprietary methods, therefore the general prerequisite for the satisfaction of all proprietary claims is that the plaintiff is obliged to prove his ownership (title)1.

Property law methods of protection are applied only in cases where the owner’s right to an individually defined thing is violated. Claims in rem are always non-contractual.

Thus, proprietary claims are non-contractual demands of the owner presented to the court for the protection of his existing right to an individually defined thing, if the right of ownership is directly violated by a specific person.

In Russian law, proprietary claims are used to protect the violated rights of subjects other than property rights, real rights, and even to protect the violated rights of legal owners.

State duty amount

Vindication is a dispute regarding property. The state fee for filing any claim of a property nature is calculated based on its price.

If the amount of the state duty turns out to be too much to pay, you can ask the court for a deferment by filing a corresponding petition. It will need to be accompanied by evidence of the impossibility of payment (certificate of income, pension, etc.).

Table: state duty calculation scheme

| Cost of claim, rub. | Fixed duty rate, rub. | Percentage of the amount exceeding the claim price | Amount when calculating interest, rub. |

| up to 20000 | — | 4% (but not less than 400 rub.) | claim price |

| 20001–100 000 | 800 | 3% | exceeding 20000 |

| 100000–200000 | 3200 | 2% | exceeding 100000 |

| 200001–1000000 | 5200 | 1% | exceeding 200000 |

| over 1000000 | 13200 | 0.5% (but not more than RUB 60,000) | exceeding 1000000 |

Vindication claim

1. Concept, subjects and grounds (conditions for satisfaction) of a vindication claim. In accordance with Art. 301 of the Civil Code “the owner has the right to reclaim his property from someone else’s illegal possession.” The formula “a vindication claim is a claim by a non-possessing owner against a non-possessing owner” has become widespread. Thus, the claim of a non-possessing owner against an illegally possessing non-owner for the seizure of a thing (object of ownership) in kind is recognized as vindication.

A vindication claim is brought when the plaintiff is simultaneously deprived of the rights to own, use and dispose of a thing, but retains the title of owner. The defendant, on the contrary, does not have any title to the property he owns - he is the untitled actual owner. Untitled possession occurs in relation to a stolen thing, an appropriated find, i.e. most often in relation to property that has been removed from the owner’s possession against his will.

A defendant who must transfer a thing to the plaintiff under any obligation is not recognized as a non-title owner. This applies both to cases where the defendant still remains the owner (for example, in case of failure to fulfill the obligation to transfer the property to the plaintiff), and to cases where the defendant received possession of the thing from the owner (for example, under a lease agreement) and continues to own it after termination of the contract. In these cases, the plaintiff must defend his violated right with obligatory (relative) claims.

Thus, the grounds for a vindication claim are:

- violation of the plaintiff’s rights to own (and therefore use and dispose of) property belonging to him;

- finding the requested item in the actual possession of the defendant;

- lack of title to the thing claimed by the defendant.

In general, the construction of a vindication claim consists of two inextricably linked components: 1) the absolute component - on the recognition of the plaintiff’s property rights; 2) the relative component - about taking away a thing from the defendant and transferring it to the plaintiff (i.e., about claiming property in kind). The inseparability of these two components is manifested in the fact that the vindication claim is not subject to satisfaction both in the case when the plaintiff has not proven his ownership rights, and in the case when the plaintiff’s ownership has been proven, but the claimed thing is in possession by the time the case is considered in court there was no defendant. The reasons why the thing left the defendant’s possession do not play a role - the owner in this case has the right to bring another claim against the defendant, this time under the law of obligations (for example, to recover the value of the thing).

The vindication claim is subject to the general limitation period (Article 196 of the Civil Code). In accordance with paragraph 1 of Art. 200 of the Civil Code, this period begins to run not from the moment when the owner lost the property, but from the moment when the owner learned or should have learned about which specific person the property being sought is in possession.

2. Proof by the plaintiff of ownership. The plaintiff proves his right of ownership by reference to the grounds for acquiring ownership rights provided for by law (Chapter 14 of the Civil Code)4. Failure by the plaintiff to prove his right of ownership or the court's conclusion that the basis for the emergence of the right is flawed entails refusal to satisfy the vindication claim, regardless of whether the fact of illegal possession by the defendant has been established.

The defendant can (and sometimes, due to the circumstances of the case, must) take an active position. Thus, the plaintiff’s arguments about his ownership rights may be paralyzed by the defendant’s evidence that he himself is the owner. Proving by the defendant that he is the owner of the disputed property on the basis of an agreement with the owner also entails refusal to satisfy the vindication claim, but this time due to the incorrectly chosen method of defense - the plaintiff in this case is not deprived of the opportunity to bring a claim under the law of obligations for recovery things.

Thus, the plaintiff’s proof of his ownership while the defendant’s lack of proof of title means that the defendant is the unlawful owner. Only in this case does it become possible to say that the owner really demands the return of his property from truly illegal possession.

3. Types of illegal possession. Illegal (titleless) possession can be in good faith or in bad faith. A bona fide owner is one who did not know and should not have known about the ownership of the disputed property by another person. For example, an heir who received someone else's property as part of an inheritance may be recognized as a bona fide owner. A thief, or a person who misappropriated a find, or a person who unauthorizedly moved into someone else’s apartment cannot be recognized as a bona fide owner (since the real owner is included in the Unified State Register and the offender should have known about it), etc.

Since in most cases ownership is transferred through civil transactions, the legislation distinguishes the figure of a bona fide and dishonest acquirer. Any acquirer who has the disputed property in his possession is also its owner. Illegal possession during the acquisition of property occurs if the property was not acquired from the owner or a person authorized by him. Accordingly, it is possible to acquire a thing into illegal possession only from a person who is not the owner and who is usually called an unauthorized alienator. An unauthorized alienator can be not only a thief, but also a tenant, custodian, etc., since these persons also do not have the right to dispose of the thing that was transferred to them by the owner under an agreement. A bona fide purchaser is one who did not know and could not know that the property he was acquiring did not belong to the alienator by right of ownership. A bona fide purchaser (and, accordingly, owner) can be recognized, for example, as a person who purchases a stolen item in a thrift store.

Thus, property can always be vindicated by the owner from an owner who is both illegal and dishonest. But if the illegal owner is a bona fide purchaser, the vindication claim is not always subject to satisfaction.

4. Restrictions on vindication in favor of the bona fide owner and purchaser. A vindication claim cannot be satisfied if three conditions are simultaneously met (Article 302 of the Civil Code):

- the property claimed by the defendant was acquired in a transaction from an unauthorized alienator for compensation;

- the property came to the unauthorized alienator at the will of the owner (or, in other words, it initially left the owner’s possession at his will);

- the acquirer of the property was in good faith at the time of acquisition.

If at least one of the first two conditions is missing, the owner has the right to reclaim the property even from a bona fide purchaser.

Thus, a stolen car, for example, is subject to reclaim from a bona fide buyer (it does not matter that the car was stolen from a guarded parking lot - the property is considered to have left the owner’s possession against his will, even if he initially transferred this property to possession by another person under contract).

For a bona fide purchaser of money or bearer securities, an additional “benefit” is established: it is only required that these types of property be acquired for compensation (i.e., a vindication claim cannot be satisfied even if the money or bearer securities were originally, for example, stolen from the owner). Order and registered securities certifying a monetary claim cannot also be demanded from a bona fide purchaser (clause 3 of Article 147.1 of the Civil Code).

If all the conditions provided for in Art. 302 of the Civil Code, a bona fide purchaser of property is recognized as the owner (i.e., Article 302 of the Civil Code provides for a special legal structure for the acquisition of property rights)1. Thus, the plaintiff is denied property rights under Art. 302 of the Civil Code due to the fact that he ceased to be the owner and has no right to a vindication claim.

5. Settlements between the plaintiff and the defendant when satisfying a vindication claim (Article 303 of the Civil Code). These calculations are a special case of calculations when returning property in connection with unjust enrichment (Chapter 60 of the Civil Code). The owner has the right to demand from the illegal owner the return or compensation of income that the owner has received or should have received during the entire period of ownership. In turn, the illegal owner has the right to demand from the owner compensation for the necessary expenses incurred on the property and compensation for the cost of inseparable improvements to the property. The amount of compensation is determined taking into account whether the illegal owner is bona fide or dishonest (naturally, an unscrupulous owner is put in a worse position than a bona fide one).

Implementation of the plaintiff’s demands: seizure of property

After the claim is satisfied, the decision made by the court must enter into legal force. The entry date will be indicated in the determination. Next, you need to find out in court whether you need to write an application for obtaining a writ of execution. If by the time it is issued the property has not been returned to the plaintiff’s use, then this writ of execution must be taken to the bailiff service (the address will be indicated in court).

If, according to a court ruling, any funds are expected to be transferred, then the writ of execution must also be given to the bailiffs, indicating bank details and passport details (and checking them three times). If the data was entered incorrectly, the money may go to another person’s account. And to get them back, you will have to go to court again.

The exception to this procedure is when the court makes a decision on the immediate return of property.

The court may, at the request of the plaintiff, enforce the decision immediately if, due to special circumstances, delaying its execution may lead to significant damage to the claimant or execution may be impossible. If it is assumed that the decision will be immediately executed, the court may require the plaintiff to ensure that its execution is reversed in the event that the court decision is overturned. The issue of immediate execution of a court decision may be considered simultaneously with the adoption of the court decision.

Clause 1 of Article 212 of the Civil Procedure Code of the Russian Federation

If the illegal owner does not give up the property voluntarily, the case is transferred to the bailiffs

It is important to remember that if a court decision is not executed before enforcement proceedings are initiated, the defendant will be responsible for paying the enforcement fee. So, if the subject of the dispute is expensive real estate, the enforcement fee can be a large amount (7% of the claim price).

Negative claim (Article 304 of the Civil Code)

The rights of the owner may be violated as a result of creating obstacles in the exercise of his powers to use his property. For example, such violations are preventing the owner from entering the premises he owns by posting security guards by the owner of the building, unauthorized construction on the owner’s land, power outages, etc.

In these cases, to protect the violated right, such a method of proprietary protection as a negatory claim is used. The owner's claim to protect property rights by eliminating violations not related to the deprivation of the owner's possession is considered negative.

Satisfying a negative claim, the court may impose an obligation on the violator to perform certain actions (for example, remove garbage), as well as to refrain from actions (for example, stop placing industrial waste on the land plot).

The limitation period does not apply to negatory claims (Article 208 of the Civil Code), unlike vindication claims. In this regard, the criterion for distinguishing between negatory and vindication requirements is of great practical importance. Such a criterion is to establish the fact of whether the thing is in the illegal possession of the violator (vindication claim) or not (negative claim). Thus, claims for eviction from residential premises are qualified as vindication claims, since the violators, living in the premises and not allowing the owner there, actually own it. On the contrary, the requirement to dismantle a sales counter installed in the hall of a non-residential building is qualified as a negatory claim, since the owner has free access to the hall of the building he owns.

Which court should I apply to?

Property law issues are considered in magistrates' and arbitration courts.

The jurisdiction of the magistrate's court includes:

- Negative claims on real estate, the court is selected according to the location of this object.

- Negative claims on movable property, the court is chosen at the place of stay (or residence) of the defendant.

In cases where one of the parties is a legal entity, the arbitration court deals with the consideration of the case for any type of claim.

If you plan to file a vindication claim on real estate, you should go to the district court where the property is located.

When it comes to the return of movable property, they turn to the district court at the place of stay (or residence) of the defendant.

back to menu ↑

Claim for the release of property from seizure or its exclusion from the inventory

In order to secure a claim or to ensure foreclosure on the debtor's property, property belonging to the debtor may be seized. Seizure of property always means a prohibition to dispose of this property, and, if necessary, additionally - restriction of the right to use the property or seizure of property. The seizure of property is carried out by a bailiff with the drawing up of an act of seizure (inventory of property). As a rule, seized property is subsequently sold by bailiffs forcibly, i.e. becomes the property of third parties.

Sometimes a seizure is imposed on property that is in the debtor's possession, but does not belong to the debtor by right of ownership. In this case, the property can be either in the possession of the owner (for example, the property of the debtor’s wife when the spouses live together) or in the possession of the debtor (for example, property rented by the debtor). In this case, the owner has the right to apply to the court to release the property from seizure. This method of proprietary protection is regulated by Art. 119 of the Law on Enforcement Proceedings.

A claim to release property from seizure or to exclude it from the inventory is a claim by the owner to lift restrictions on the disposal of property, aimed at preventing the sale of seized property in the future.

Sometimes the seized property is transferred by the bailiff to a third party for protection or storage. In this case, the owner must, in addition to the claim for the release of property from seizure, file a vindication claim against the actual owner. If the seized property has already been sold by bailiffs, then the owner can only bring a vindication claim against the actual owner.

Objects, subjects and subjects

The object of such a claim is specific property that is in the unauthorized possession of another person.

Moreover, if it is impossible to reduce everything to one thing in common, items that have common properties for everyone in this category fall under vindication.

For example: fuel; Construction Materials; seedlings, etc. If it is impossible to single out something specific from the general mass, then the claim will be based on unjust enrichment of the owner.

The subject (that is, who is held accountable for the claim) is actually the person who illegally took possession and disposes of the property.

The subject of a vindication claim is a demand to return to the owner his thing from unauthorized possession.

Other proprietary methods of protection

Theory and judicial practice have developed proprietary methods of protection, which are not yet directly specified in the Civil Code.

Basically, these are methods of protecting the right of ownership of real estate, the specificity of which is explained by the fact that the only acceptable evidence of ownership of this property is an entry in the Unified State Register.

The most widespread in practice is the claim for recognition of property rights. The main features of a claim for recognition of property rights are: 1) this claim is not aimed at confiscating property from anyone; 2) the statute of limitations does not apply to claims for recognition of ownership rights. Based on these features, in fact, a claim for recognition of property rights can only be satisfied if it is brought by the plaintiff-owner, who owns his property, against the defendant, who does not recognize the plaintiff’s property rights. In the case where the plaintiff does not own the real estate, the requirement for recognition of ownership rights can be satisfied only within the general limitation period - it is believed that in this case the violated right cannot be protected only by recognition of ownership rights without considering a vindication claim.

There is a claim to declare a right or encumbrance absent.

This method of protecting the right of ownership of real estate is used when an entry in the Unified State Register violates the rights of the owner of the real estate, but there is no basis for using the methods of proprietary protection discussed above. It is required to recognize the registered ownership right of a third party as absent (non-existent) when the ownership right to the same piece of real estate is erroneously registered for both the plaintiff and another entity (it is clear that this creates uncertainty in the ownership of the object) or when the ownership right for movable property the property is registered as real estate (for example, a path passing through the owner’s land). It is required to recognize a registered encumbrance on real estate as absent (non-existent) when the encumbrance has actually ceased, but the entry from the Unified State Register has not been deleted (for example, the mortgage has ceased due to the repayment of the loan, but the bank refuses to submit an application to remove the mortgage)1.

What should be included with the application to the court?

In addition to the application itself, the plaintiff will need to submit a package of documents. Among them:

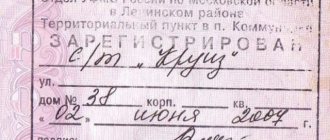

- Copies of forms evidencing the plaintiff’s ownership.

- Documents documenting that this right is violated as a result of the actions of the defendant.

- Calculation of damage caused.

- Receipt for payment of state duty.

If one of the parties (and possibly both) are legal entities, extracts from the Unified State Register should be attached to the form.

In any case, a second copy of the application is prepared, which will remain with the defendant.

back to menu ↑